Many of the products on the market indicate we are under a full-scale war with bacteria. Everything from our antibiotic-rich food supply, soaps and detergents, hand sanitizers, disinfectants, mouthwashes, and even garbage bags tout their anti-bacterial properties. Seeing this, one could be left with the impression that bacteria are bad for our health and must be eliminated; what we fail to realize is humans are bacterial, too.

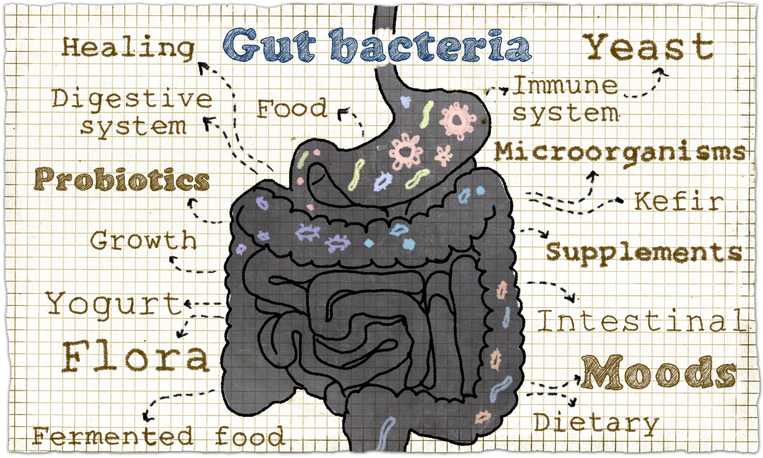

There are 100 trillion microbes (tiny organisms including bacteria, viruses, fungus, yeast, etc.) living inside and on our bodies. The major function of these microbes is to create a healthy environment for our bodies and immune system by keeping the balance between “good” and “bad” microbes. Our “microbiome” refers to an individual’s collective community of bacteria, fungi, yeast, and other tiny organisms, and located in our oral and nasal cavities, skin, genital-urinary and gastro-intestinal tract. Our microbiome helps breakdown food, makes nutrients for absorption, neutralizes toxins in the body, and protects us from illness.

There are 100 trillion microbes (tiny organisms including bacteria, viruses, fungus, yeast, etc.) living inside and on our bodies. The major function of these microbes is to create a healthy environment for our bodies and immune system by keeping the balance between “good” and “bad” microbes. Our “microbiome” refers to an individual’s collective community of bacteria, fungi, yeast, and other tiny organisms, and located in our oral and nasal cavities, skin, genital-urinary and gastro-intestinal tract. Our microbiome helps breakdown food, makes nutrients for absorption, neutralizes toxins in the body, and protects us from illness.

Probiotics, Prebiotics & Antibiotics: What is the difference?

So, what is the difference between all these “biotics”? Biotic, by definition, means related to or resulting in “living things.” That is the critical feature when discussing foods with “biotic” properties — they contain a living organism. Probiotics are microorganisms naturally present in the digestive tract that aid in digestion and reduce inflammation, among other things. We can also ingest live bacteria that will take up residence and thrive in our gut. One of the most common foods we hear of being associated with probiotics is yogurt. Not all yogurts are probiotic, though; yogurts must contain live cultures to be considered probiotic.

Pasteurization, in use since the early-to- mid -1900’s, kills off all bacteria, damages vitamins to the point of being unusable by the body, and destroys the naturally present enzyme that allows the body to digest the milk. There are health risks associated with raw milk (severe infections caused by harmful bacteria), so when making live culture yogurt, live bacteria are added to pasteurized milk and allowed time to ferment and grow. This process allows for the good bacteria and healthy enzymes in the dairy to flourish. The problem is that some yogurt products are heat-treated after fermentation, which kills most of the beneficial active cultures found in the yogurt. Therefore, not all yogurt sold in the supermarket contain live cultures, so consumers must look for the “Live & Active Culture” seal.

Pasteurization, in use since the early-to- mid -1900’s, kills off all bacteria, damages vitamins to the point of being unusable by the body, and destroys the naturally present enzyme that allows the body to digest the milk. There are health risks associated with raw milk (severe infections caused by harmful bacteria), so when making live culture yogurt, live bacteria are added to pasteurized milk and allowed time to ferment and grow. This process allows for the good bacteria and healthy enzymes in the dairy to flourish. The problem is that some yogurt products are heat-treated after fermentation, which kills most of the beneficial active cultures found in the yogurt. Therefore, not all yogurt sold in the supermarket contain live cultures, so consumers must look for the “Live & Active Culture” seal.

Prior to pasteurization and sanitization of our food supply, people ate much more bacteria in terms of both the number of bacteria and diversity of those bacteria. Many vegetables were fermented (pickles, sauerkraut, kimchi), mainly for the purpose of food preservation, and gave people more access to a diverse offering of healthy bacteria. Also, many people depended on home gardens to obtain their vegetables, so they ate more food that had dirt residue on it, which are also teeming with the types of bacteria most beneficial to our health. In our desire to kill off all potentially dangerous pathogens, we have over-sanitized ourselves to the point of starving the bacteria and micro-organisms, which our bodies rely on to maintain optimal health.

Prior to pasteurization and sanitization of our food supply, people ate much more bacteria in terms of both the number of bacteria and diversity of those bacteria. Many vegetables were fermented (pickles, sauerkraut, kimchi), mainly for the purpose of food preservation, and gave people more access to a diverse offering of healthy bacteria. Also, many people depended on home gardens to obtain their vegetables, so they ate more food that had dirt residue on it, which are also teeming with the types of bacteria most beneficial to our health. In our desire to kill off all potentially dangerous pathogens, we have over-sanitized ourselves to the point of starving the bacteria and micro-organisms, which our bodies rely on to maintain optimal health.

Antibiotics Fight Bacteria

If you’ve made a couple doctor’s visits in your life you may be familiar with antibiotics. Antibiotics, also known as antibacterial, are bacteria fighters. They are medications that combat bacteria by either destroying them or keeping them from growing. The only problem is that not all antibiotics are selective in their bacterial destruction, meaning they can destroy the good bacteria, too. Antibiotics will also have no effect on a virus, but doctors rarely culture for the cause of an infection or illness before prescribing an antibiotic. Overuse of antibiotics can cause bacteria to change, so antibiotics don’t work against them. This is called bacterial resistance, or antibiotic resistance. Treating these resistant bacteria requires higher doses of medicine or stronger antibiotics. Because of antibiotic overuse, certain bacteria have become resistant to even the most powerful antibiotics available today.

If you’ve made a couple doctor’s visits in your life you may be familiar with antibiotics. Antibiotics, also known as antibacterial, are bacteria fighters. They are medications that combat bacteria by either destroying them or keeping them from growing. The only problem is that not all antibiotics are selective in their bacterial destruction, meaning they can destroy the good bacteria, too. Antibiotics will also have no effect on a virus, but doctors rarely culture for the cause of an infection or illness before prescribing an antibiotic. Overuse of antibiotics can cause bacteria to change, so antibiotics don’t work against them. This is called bacterial resistance, or antibiotic resistance. Treating these resistant bacteria requires higher doses of medicine or stronger antibiotics. Because of antibiotic overuse, certain bacteria have become resistant to even the most powerful antibiotics available today.

There are times where antibiotic use is unquestionably required. What becomes problematic is our exposure to antibiotics has become pervasive across all areas of our lives; including premature use of antibiotics in healthcare for routine colds and misdiagnosed viral infections, widescale use in food production, general overuse in personal care products, and various household products that sanitize environments.

There are times where antibiotic use is unquestionably required. What becomes problematic is our exposure to antibiotics has become pervasive across all areas of our lives; including premature use of antibiotics in healthcare for routine colds and misdiagnosed viral infections, widescale use in food production, general overuse in personal care products, and various household products that sanitize environments.

All of these instances result in lower, yet necessary, exposure to bacteria in our daily lives. If we allow our bodies to exist in a way that is more friendly to bacteria (such as not feeling compelled to sterilize our environment), and don’t overexpose ourselves to antibiotics in our food and personal care products, we will be in a better position to respond and recover when we do need to use antibiotics.

Prebiotics & Probiotics to the Rescue

Research has shown that we can rebuild our gut microbiota after antibiotic use, but we face potentially permanent loss of certain beneficial bacteria after multiple exposures to antibiotics during our lifetime. Most beneficial to restoring our health after antibiotic use is exploring a regimen of prebiotics and probiotics. Prebiotics are certain types of indigestible carbohydrates that act as food for the good bacteria already in our gut. Prebiotics rich foods are broccoli, whole grain, cabbage, kale, and cauliflower. Probiotic food sources are aged cheeses, such as cheddar, gouda, or mozzarella, kefir, a probiotic milk drink, traditional buttermilk (must not be cultured), live culture yogurt, fresh, sour dill pickles, kombucha, a fermented tea, and miso to name a few.

Both prebiotics and probiotics are needed to rebuild the healthy bacteria in our gut after they are killed off by antibiotic use.

Despite the proliferation of commercially available probiotics products and supplements, one study found that out of 14 commercial probiotics, only one contained the species stated on the label. Like most health-related challenges, it appears that there is no easy substitute for eating healthy, whole foods when it comes to the health of our microbiome. Given that for every human cell in our body there are 10 resident microbes, we need to rethink our food intake to include the nutritional needs of our microbiome.

Internal Biodiversity as a Driver of Health

There is evidence that Western populations have a considerably lower diversity (fewer types of bacteria) of their gut microbiota. Western diets — typically high in fats, sugar, simple carbohydrates, and processed foods — are implicated in the changing of the microbiome. Immigrants within 6 months of moving to the US and eating the Standard American Diet (SAD) lose their native microbes. Research indicates that the loss of diversity is significant — immigrants lost 15 percent of microbiome diversity.

There is evidence that Western populations have a considerably lower diversity (fewer types of bacteria) of their gut microbiota. Western diets — typically high in fats, sugar, simple carbohydrates, and processed foods — are implicated in the changing of the microbiome. Immigrants within 6 months of moving to the US and eating the Standard American Diet (SAD) lose their native microbes. Research indicates that the loss of diversity is significant — immigrants lost 15 percent of microbiome diversity.

Animal experiments suggest that a diet and lifestyle that leads to different microbes being introduced and maintained in the gut has a direct effect on obesity. Incorporating foods into our diet that directly introduce and nourish healthy bacteria can have a significant impact on our health in terms of weight management, mood, chronic illness development, and immunity building.

Though more research is needed to understand the role our gut health plays in our overall wellness, we can turn to the food traditions of our ancestors as a guide. Almost every culture on earth has a robust history of using fermented foods in their diets; the earliest record of fermentation dates back as far as 6000 B.C.! Fermentation allows the healthy bacteria, already found on and in foods, to grow and multiply.

Eating live foods is a great first step in rebuilding the biodiversity of our microbiomes, but they are not powerful enough to counteract the damage of a SAD diet. Given that our microbiomes have been linked to everything from arthritis, obesity, depression, and autoimmune illness, it may be worth rethinking our diets. Preliminary research indicates that our gut bacteria play a role in our food cravings. Once we establish a dominance of healthy bacteria in our gut, our bodies will be less likely to crave and rely on the foods that will destroy it.

Thanks Jennifer for this amazing article. We are so grateful to Focus for Health for all you do for our autism community!