Raise your hand if you’ve heard any of the following, whether it was said to you or in your presence:

Raise your hand if you’ve heard any of the following, whether it was said to you or in your presence:

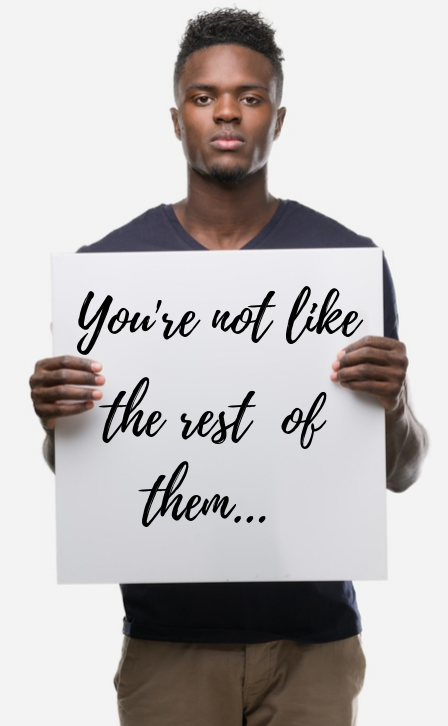

- “You’re not like the others” when referring to your racial background, religion, or gender

- “Is that your real hair?”

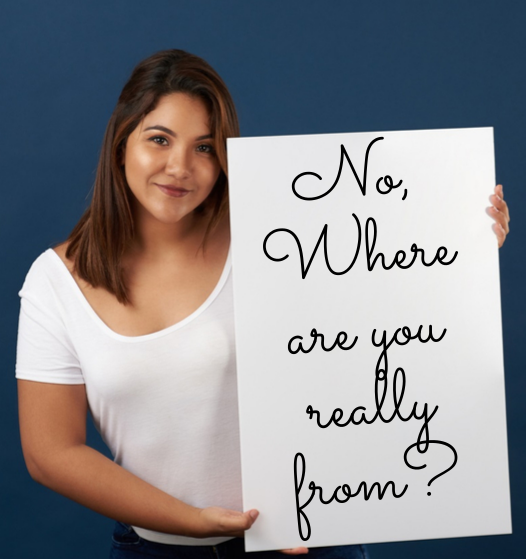

- “What do you mean you don’t speak Spanish?” when referring to someone of Latino origin

- “You’re very pretty for a dark skinned woman”

If you’ve heard any of the previous statements, then you had a firsthand experience with micro-aggressions. When these statements are made, people often feel something isn’t quite right, but usually can’t quite figure out what’s not right. First, let’s define what a microaggression is

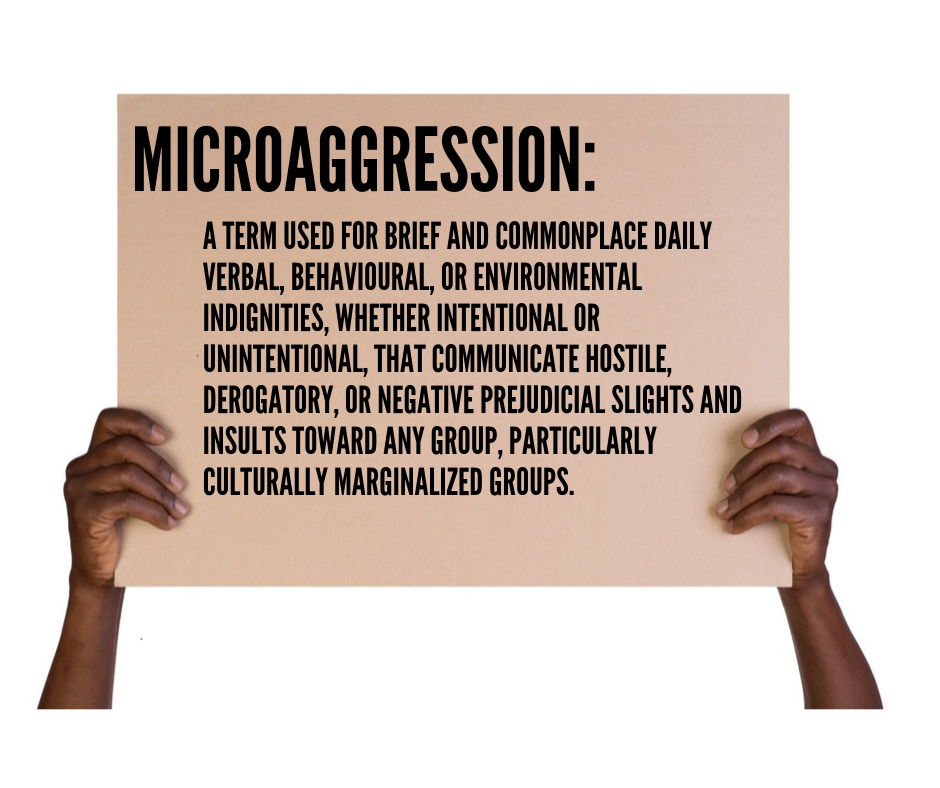

How Do We Define Microaggressions?

As defined by psychologist D.W. Sue, who has studied the topic extensively, a microaggression is a “brief and commonplace slight/insult that communicates hostility or prejudice towards particular groups of people”. The term was coined by Harvard professor Chester M. Pierce in 1970 in response to insults and dismissals he witnessed inflected on black Americans. While many argue against the validity of microaggressions based on the fact that it’s an entirely subjective claim, when presented with examples, an overwhelming majority of us recognize these phrases.

As defined by psychologist D.W. Sue, who has studied the topic extensively, a microaggression is a “brief and commonplace slight/insult that communicates hostility or prejudice towards particular groups of people”. The term was coined by Harvard professor Chester M. Pierce in 1970 in response to insults and dismissals he witnessed inflected on black Americans. While many argue against the validity of microaggressions based on the fact that it’s an entirely subjective claim, when presented with examples, an overwhelming majority of us recognize these phrases.

Researchers typically cite 3 types of microaggressions:

- Micro-insults: Communications that unintentionally demean someone’s identity

- Micro-assault: Discriminatory name-calling. This is the only intentional form of microaggressions.

- Microinvalidations: Communications that exclude or negate the thoughts, feelings, or experiences of marginalized groups

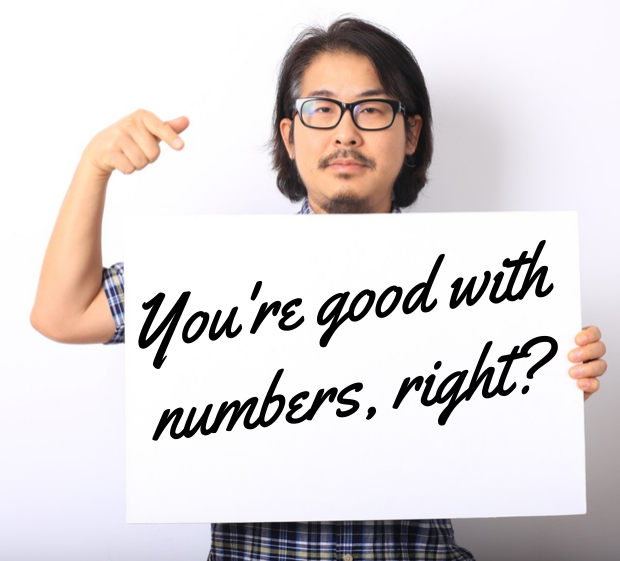

Microaggressions are not always racially or ethnically based. Think about preconceived notions people have about the poor, the homeless, those of different sexualities, or even the neighborhood one lives in. Stereotypes play into microaggressions as well, and many stereotype-based compliments serve as microaggressions. Making a comment about a female Asian co-worker being docile or deferential would be a combination of both gender and ethnic microaggressions, as well as a comment about how feisty or confrontational a Latina co-worker is.

How Unconscious Bias Shaped Microaggressions

As previously mentioned, only microassaults are intentional microaggressions, and even the intentional ones are a result of either unconscious or conscious bias. Unconscious (or implicit) bias is defined as attitudes, perceptions, and stereotypes that unknowingly influence our actions and behaviors when interacting with various identities. This bias is developed through an “exposure to stereotypes and misinformation according to our upbringing and life experiences”. Unconscious bias can often explain why people with no conscious intentions to be bigoted may say something that qualifies as a microaggression.

As previously mentioned, only microassaults are intentional microaggressions, and even the intentional ones are a result of either unconscious or conscious bias. Unconscious (or implicit) bias is defined as attitudes, perceptions, and stereotypes that unknowingly influence our actions and behaviors when interacting with various identities. This bias is developed through an “exposure to stereotypes and misinformation according to our upbringing and life experiences”. Unconscious bias can often explain why people with no conscious intentions to be bigoted may say something that qualifies as a microaggression.

For example, take an experiment done at Harvard Business School. The experiment found that employers favor men when hiring, not because they are prejudiced against women, but because they have conscious and unconscious bias that men perform their jobs better than women. In this example, imagine a male boss giving his most important assignments to his male co-workers. He may not ask himself why all his important work goes to other men, but in this case, it may be his unconscious bias pulling him in one direction.

It’s noteworthy to state that, according to The Kirwan Institute, everyone has unconscious biases, and we generally tend to hold unconscious bias that favors the groups we belong to. It’s tempting to believe that because we are all unconsciously biased, that it may not be as bad as one would think. However, the science behind the consequences of microaggressions and unconscious bias paints a bleak picture.

The Dangers of Microaggressions and Unconscious Bias

A 2012 study published in the American Journal of Public Health was designed to examine the association between pediatricians attitudes about race and how they conducted their work. The results showed that as pro-White implicit bias increased, narcotic prescribing decreased for Black patients but not white patients. This study coincides with the findings of a study published this year (2019) in PLoS One regarding microaggressions in health care. That study found that racial microaggressions were positively correlated with discrimination, and that higher levels of perceived microaggressions were correlated with psychological distress symptoms, which mirrors the results of a study published in the Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. That study established that in Native American health care, microaggressions were significantly associated with heart attack history, past year hospitalization, and depressive symptoms.

A 2012 study published in the American Journal of Public Health was designed to examine the association between pediatricians attitudes about race and how they conducted their work. The results showed that as pro-White implicit bias increased, narcotic prescribing decreased for Black patients but not white patients. This study coincides with the findings of a study published this year (2019) in PLoS One regarding microaggressions in health care. That study found that racial microaggressions were positively correlated with discrimination, and that higher levels of perceived microaggressions were correlated with psychological distress symptoms, which mirrors the results of a study published in the Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. That study established that in Native American health care, microaggressions were significantly associated with heart attack history, past year hospitalization, and depressive symptoms.

For African American women, childbirth can be a daunting task due to a maternal mortality rate nearly three times the national average. With mortality rates so high, one has to posit that either African American women are inherently more likely to die during childbirth (which is ludicrous), or that there is something fundamentally wrong with the way we treat black women during their pregnancy. According to Neel Shah, an obstetrician-gynecologist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, “the common thread is that when black women expressed concern about their symptoms, clinicians were more delayed and seemed to believe them less. It’s forced me to think more deeply about my own approach. There is a very fine line between clinical intuition and unconscious bias.” A series of focus groups conducted by the Mississippi State Department of Health found that many black women avoided prenatal care because of how providers treated them, and because their choice of providers was limited, many of them simply didn’t receive prenatal care. This troubling trend is also evidenced by the fact that black men with black doctors receive more effective care than those without black doctors, showing that access and quality of care can be undone by unconscious bias or preconceived notions.

Health care is not the only place where microaggressions can wreak havoc on the victims. In the workplace, women of color (particularly black women) experience bias related to their hair style or texture. As Evan Auguste of Scholars Strategy Network puts it:

“Qualitative work has shown that daily exposure to microaggressions can create hostile spaces… People confronted by microaggressions often see them as reminders that their peers may believe they belong to a lower social class, simply because of their race…These passing comments can confuse and disarm the receiver while they attempt to decipher the meaning and intent of the comment. Only after deciphering the meaning of the comment do they then have to decide how to respond. Some researchers posit that even if minority group members do not respond directly to each instance, microaggressions can gradually tax racial minority group members’ coping mechanisms — at times pushing them into extreme distress.

Addressing Our Own Unconscious Bias

Even though we all fall victim to unconscious bias, it does not have to remain that way. One of the simplest ways of addressing unconscious bias is bringing it to the front of our minds and making a conscious decision to acknowledge it. Learning more about bias, in general, and how it affects our decision making and behaviors is a critical first step. A paper published in the Journal of General Internal Medicine found that when asking physicians to diagnose a hypothetical patient identified as white or black, the physicians who were made aware of the purpose of the study performed better and compensated for their biases when made sensitive to the risk of their own bias.

Even though we all fall victim to unconscious bias, it does not have to remain that way. One of the simplest ways of addressing unconscious bias is bringing it to the front of our minds and making a conscious decision to acknowledge it. Learning more about bias, in general, and how it affects our decision making and behaviors is a critical first step. A paper published in the Journal of General Internal Medicine found that when asking physicians to diagnose a hypothetical patient identified as white or black, the physicians who were made aware of the purpose of the study performed better and compensated for their biases when made sensitive to the risk of their own bias.

When addressing institutional bias leading to microaggressions, The UC-San Francisco Office of Diversity and Outreach recommends developing concrete & objective indicators and outcomes for hiring, evaluation, and promotion. They also recommend unconscious bias training for all decision-making constituents involved, such as executives and senior staff. The Center for Health Journalism recommends online resources for employees that assists them in “understanding the nature and impact of microaggressions”. Prevention is the strongest tool in this fight. While it’s impossible to predict an upcoming microaggression, being proactive in dispelling and/or screening for bigoted beliefs is crucial to the integrity of institutions nationwide.

Join the Conversation