New Jersey is experiencing a maternal health crisis, with an unbelievable 37 per 100,000 women dying around the time of giving birth. Ranking 47th out of 50 states in overall maternal mortality, this problem exposes a significant racial inequality. African-American mothers die at 3-4 times the rate that white or Hispanic mothers do, even when factoring out socio-economic status.

New Jersey is experiencing a maternal health crisis, with an unbelievable 37 per 100,000 women dying around the time of giving birth. Ranking 47th out of 50 states in overall maternal mortality, this problem exposes a significant racial inequality. African-American mothers die at 3-4 times the rate that white or Hispanic mothers do, even when factoring out socio-economic status.

The birth of a child should be a joyful experience in a woman’s life; instead, it becomes her last act, leaving a motherless child and an entire family bereft. Add to that the current research showing 60% of these deaths were deemed preventable, and you have the makings of an unimaginable tragedy.

Tammy Murphy, First Lady of New Jersey, is determined to reverse this state-wide infant and maternal mortality trend. On Maternal Health Day 2019, she unveiled her plan, Nurture NJ, to raise awareness and eliminate racial disparities in maternal healthcare.

Indeed, with the array of new maternal health-focused legislation being voted on in Trenton this session, New Jersey is poised to make a significant impact. And it’s none too soon – families across the state need citizens to show they care about mothers by putting concrete solutions in place to reduce maternal mortality.

Indeed, with the array of new maternal health-focused legislation being voted on in Trenton this session, New Jersey is poised to make a significant impact. And it’s none too soon – families across the state need citizens to show they care about mothers by putting concrete solutions in place to reduce maternal mortality.

Why is this happening?

There are many theories about the causes of maternal mortality, which is sometimes referred to in the data as pregnancy-related deaths. These deaths are defined as “the death of a woman while pregnant, or within one year of termination of pregnancy, irrespective of the duration and site of pregnancy, from any cause related to or aggravated by her pregnancy or its management, but not from accidental or incidental causes.” (Hoyert 2007). Factors such as lack of prenatal care, preexisting medical conditions, healthcare worker indifference, and excessive interventions, are all potential contributors.

There are many theories about the causes of maternal mortality, which is sometimes referred to in the data as pregnancy-related deaths. These deaths are defined as “the death of a woman while pregnant, or within one year of termination of pregnancy, irrespective of the duration and site of pregnancy, from any cause related to or aggravated by her pregnancy or its management, but not from accidental or incidental causes.” (Hoyert 2007). Factors such as lack of prenatal care, preexisting medical conditions, healthcare worker indifference, and excessive interventions, are all potential contributors.

As one of the foremost maternal health researchers, Neel Shah, MD, an assistant professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Harvard Medical School, says, “Our way of childbirth is the costliest in the world. Our health outcomes, from mortality rates to birth weights, are far, far from the best. [But] the reasons we fall short are not obvious.”

The top 5 causes of pregnancy-related deaths are Cardiac (16.7%), Cardiomyopathy (10.3%), Embolism (9.0%), Septic Shock (9.0%), and Cerebral Hemorrhage (7.7%). Out of the total number of pregnancy-related deaths, 56.4% of mothers had chronic health conditions, and 43.6% were overweight or obese. The rise in hypertensive disorders, including preeclampsia, is of particular note. These issues, which are 60% more common in African-American mothers, also tend to be more severe in this population when they do occur.

Looking at the state of women’s health overall, it was found that the death rate of women of reproductive age (15-45) has also been on the rise. Between 2010 and 2016, the rate of death in this age group has gone up 14%. Sadly, women’s health has been declining across the country, and so when we look at maternal mortality, it is just one aspect of this trend.

Identifying the Reasons

Skipping Prenatal Care

While the rate of pregnant women receiving no prenatal care has been going down since the 1970’s, lack of prenatal care is still a factor in maternal mortality. In 2016, the WHO raised their recommendation from 4 to at least 8 prenatal (antenatal) visits with a healthcare provider during pregnancy, in order to improve health outcomes for both moms and babies.

Health Factors in Pregnancy & Beyond

Chronic conditions like Type 2 diabetes, gestational (pregnancy) diabetes, high blood pressure, and asthma compound the risk for women giving birth. Drug use and smoking represent an additional layer of risk. Managing a pregnancy with one or more of these chronic illnesses or risk factors is complicated, especially if a woman doesn’t have access to quality care, either due to socio-economic factors or just a lack of education. Women need to know how important prenatal care is for both mom and baby throughout pregnancy, in order to catch issues before they become dire emergencies.

Chronic conditions like Type 2 diabetes, gestational (pregnancy) diabetes, high blood pressure, and asthma compound the risk for women giving birth. Drug use and smoking represent an additional layer of risk. Managing a pregnancy with one or more of these chronic illnesses or risk factors is complicated, especially if a woman doesn’t have access to quality care, either due to socio-economic factors or just a lack of education. Women need to know how important prenatal care is for both mom and baby throughout pregnancy, in order to catch issues before they become dire emergencies.

Listening to Mothers

Another contributing factor involves providers listening to mothers, and actually believing them. Take Serena Williams, for example, who detailed her frightening postpartum experience after the birth of her daughter in 2018. Even though as an athlete she was very in tune with her body, and was also a well-educated maternity patient, she still almost died.

Another contributing factor involves providers listening to mothers, and actually believing them. Take Serena Williams, for example, who detailed her frightening postpartum experience after the birth of her daughter in 2018. Even though as an athlete she was very in tune with her body, and was also a well-educated maternity patient, she still almost died.

Serena experienced a pulmonary embolism, a blood clot in the lungs, after her emergency C-section. Because she knew this was a complication of childbirth, and knew her own history of blood clots, she notified her doctor right away when she began having shortness of breath. Frustrated when she was not listened to right away, she had to insist on getting scanned for clots. Being a vocal, informed patient saved her life, but other women are not so lucky, especially African-American women.

“Doctors aren’t listening to us, just to be quite frank,” Serena said in a BBC interview in March 2018. “She was great. I had a wonderful, wonderful doctor. Unfortunately, a lot of African-Americans and black people don’t have the same experience that I’ve had.”

Simone Landrum of New Orleans had a similar experience during her pregnancy with her third child, when, unbeknownst to her, she developed preeclampsia, presenting with headaches and swelling as a result of borderline elevated blood pressure. The doctor dismissed her symptoms, barely noting her hypertensive episodes in her chart. He felt the increasingly intense headaches didn’t mean anything, yet a few weeks later Simone hemorrhaged suddenly, and her baby girl was stillborn, delivered via c-section.

Too Much Care vs. Not Enough

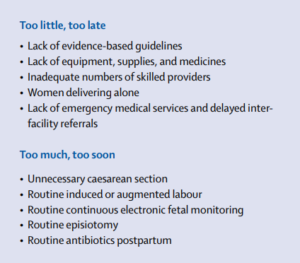

In 2016, The Lancet published a series on Maternal Health, concluding that poor care is present in all countries studied, and falls into 2 categories: either too little too late, or too much too soon. For example, Dr. Shah notes that in Texas doctors are 50% more likely to intervene and do a C-section to save a baby as doctors in New Mexico. However, infants in Texas have a 50% lower survival rate than New Mexican infants.

In 2016, The Lancet published a series on Maternal Health, concluding that poor care is present in all countries studied, and falls into 2 categories: either too little too late, or too much too soon. For example, Dr. Shah notes that in Texas doctors are 50% more likely to intervene and do a C-section to save a baby as doctors in New Mexico. However, infants in Texas have a 50% lower survival rate than New Mexican infants.

The true measure of what a woman will experience in birth, whether too many interventions or too few, are completely dependent on the hospital facility where she chooses to give birth. Even hospitals less than 5 miles apart can have vastly different C-section rates. It all depends on the OB/Gyn practices who deliver at those hospitals. If women aren’t aware of these differences, or of which interventions to try and avoid, they will be vulnerable to harm.

As one can see, there are many areas to investigate, but almost no easy answers or quick fixes.

According to 2016 data, NJ ranks 4th in the nation for the highest c-section rate. When researching the complexities behind this rate, a mix of factors has been driving it up in this highly litigious state. For instance, if a doctor has done a c-section, in the end, they are considered to have done all they can to save their patients and most likely wouldn’t lose a future malpractice lawsuit. Therefore, many doctors intervene too quickly, raising the rate and also decreasing maternal and infant health outcomes.

According to 2016 data, NJ ranks 4th in the nation for the highest c-section rate. When researching the complexities behind this rate, a mix of factors has been driving it up in this highly litigious state. For instance, if a doctor has done a c-section, in the end, they are considered to have done all they can to save their patients and most likely wouldn’t lose a future malpractice lawsuit. Therefore, many doctors intervene too quickly, raising the rate and also decreasing maternal and infant health outcomes.

In terms of compensation, doctors are paid almost twice as much for cesareans as for vaginal births. Waiting for a mom to labor and birth naturally takes many more hours than performing a c-section. Laboring mothers take up bed space, sometimes for days, and require extra care, so some doctors aren’t able to let birth unfold in its own time. This shows that, unfortunately, a fear of lawsuits, plus a complex interaction of hospital- and doctor-related time constraints, are the primary drivers of this upward trend.

Tracking the Data

In 2018, Review to Action, an organization working to prevent maternal mortality by standardizing the data tracking, reviewed reports from 9 maternal mortality review committees (MMRCS) and found that most pregnancy related deaths are preventable, and there are obvious areas for improvement and prevention. Many of these deaths are attributable to a lack of social support during pregnancy and after birth, once the mother goes home to her family and community with her newborn child.

Check back for Part 2: Solving the Maternal Health Crisis in New Jersey

I think that some discussion of maternal vaccine history is warranted when we want to determine why so many women (especially African-American) are dying during pregnancy. I understand that currently, most women receive 2 or 3 vaccines during pregnancy, even though vaccines are not safety tested for use during pregnancy. It has already been noted that at least some flu vaccines seem associated with miscarriage. Is anyone looking at the vaccine history of the mother or the number of vaccines she may have received during her pregnancy? In addition to a high rate of maternal deaths, NJ also has a very high rate of autism. Are these two outcomes related somehow?