Since 1945, the United States has been regarded as the most powerful country in the world – in Gross Domestic Product (GDP), military might, and boasting the highest quality of life. However, a closer look at our education index, health outcomes, and other indicators of the state’s well-being tell a different story. The most daunting statistic was our alarmingly high infant mortality rates (IMR). In a 50 year time trend analysis published in January 2018, compared to 19 other members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), babies born in the U.S. were nearly 3 times more likely to die from premature birth and 2.3 times more likely to experience sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS).

Since 1945, the United States has been regarded as the most powerful country in the world – in Gross Domestic Product (GDP), military might, and boasting the highest quality of life. However, a closer look at our education index, health outcomes, and other indicators of the state’s well-being tell a different story. The most daunting statistic was our alarmingly high infant mortality rates (IMR). In a 50 year time trend analysis published in January 2018, compared to 19 other members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), babies born in the U.S. were nearly 3 times more likely to die from premature birth and 2.3 times more likely to experience sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS).

Issue

How can the United States have a higher IMR than 19 other countries? Is the cause socioeconomic status — the closer someone is to poverty, the higher the likelihood of complications during pregnancy? Could it be political factors — lawmakers favoring special interest as opposed to their constituent’s well-being? Or perhaps cultural differences? Comparing the United States to 3 other nations with lower IMR — Japan, Finland, and Cuba — yields very interesting results.

U.S. Socioeconomics & The Infant Mortality Rate

Preterm birth rates have been proven again and again to vary inversely, meaning as income shrinks, the risks increase. A careful examination can yield a multitude of reasons: minimal access to health care, lack of knowledge of available resources, environmental factors, and more.

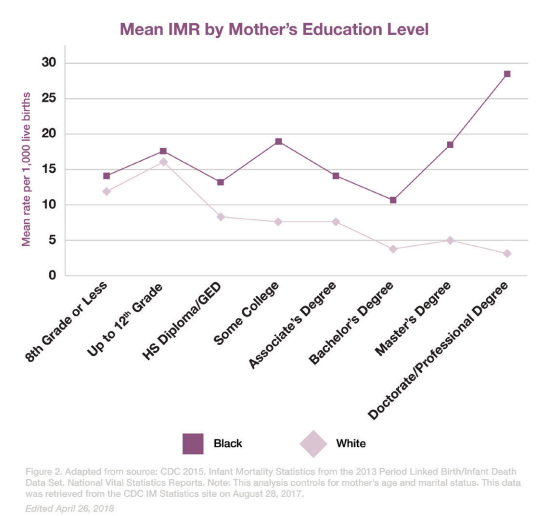

It should come as no surprise that racism, isolation and social factors play a huge role along with women in poverty, in having a higher chance of delivering a preterm baby or a child dying from SIDS. A mind-blowing study that Duke University published in March 2018, showed that, African American women with master’s and doctorate degrees have higher IMR than do white high school dropouts!

It should come as no surprise that racism, isolation and social factors play a huge role along with women in poverty, in having a higher chance of delivering a preterm baby or a child dying from SIDS. A mind-blowing study that Duke University published in March 2018, showed that, African American women with master’s and doctorate degrees have higher IMR than do white high school dropouts!

Note the dramatic spike in infant mortality rates in the graph below as African American women attain higher levels of education. The author of this study suggests that the reason for the exceptionally high IMR is because of, “increased experiences of discrimination and stress as they attain higher levels of education.”

Breaking this down further, newborns of African American women were estimated at 14% of preterm births while the rate of preterm births among white women was considerably lower at 9%. According to the U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health, in 2014, “African American mothers were 2.2 times more likely than non-Hispanic white mothers to receive late or no prenatal care and African American infants were 3.2 times as likely to die from complications related to low birthweight as compared to non-Hispanic white infants.”

Breaking this down further, newborns of African American women were estimated at 14% of preterm births while the rate of preterm births among white women was considerably lower at 9%. According to the U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health, in 2014, “African American mothers were 2.2 times more likely than non-Hispanic white mothers to receive late or no prenatal care and African American infants were 3.2 times as likely to die from complications related to low birthweight as compared to non-Hispanic white infants.”

These numbers are astonishing.

According to the 2013 report from the Duke University’s Samuel DuBois Cook Center on Social Equity and Insight Center for Community Economic Development “the white IMR in the United States was five per 1000 live births — resembling economically advanced nations like New Zealand. In contrast, the black IMR was 11.2 per 1000 live births — a rate closer to that of lower income nations like Thailand, Romania, and Grenada.”

With rising healthcare costs, disparities in health care access, a shrinking middle class, overt and unconscious racism in health care, lack of resources in underprivileged neighborhoods, and increased difficulty of accessing government programs, America’s infant mortality rates look to remain on the same trajectory for the foreseeable future. But encouragingly, there is a growing movement to support woman of color to seek alternative, non-medical, routes such as midwives and doulas, which have been shown to improve outcomes overall.

Introduction of Midwives to America

Many associate midwives with suburban middle-class Caucasian moms but, the practice of midwifery was introduced to the United States in the 17th century, through the Atlantic Slave Trade. Women pioneers such as Margaret Charles Smith, Mary Coley, and Ms. Arilla Smiley all fought for women’s rights to be able to birth the way they want to. Midwifery can be traced back to West Africa where it is a large part of their birth culture. The concept of a midwife here has become more of a luxury due to costs and the lack of government funding assistance.

Many associate midwives with suburban middle-class Caucasian moms but, the practice of midwifery was introduced to the United States in the 17th century, through the Atlantic Slave Trade. Women pioneers such as Margaret Charles Smith, Mary Coley, and Ms. Arilla Smiley all fought for women’s rights to be able to birth the way they want to. Midwifery can be traced back to West Africa where it is a large part of their birth culture. The concept of a midwife here has become more of a luxury due to costs and the lack of government funding assistance.

A large, cohort study showed that women who received government assistance and were seen by a midwife for prenatal care had significantly lower likelihood of preterm birth and low birth weight babies. So, would government assistance in alternative care help women in low socioeconomic statuses, and possibly lowering racial disparities within health care? Has it worked in other countries?

Analyzing Other Nations

Finland, Japan, and Cuba are all three very different nations, but all boast a lower IMR than the United States. Look at how they approach birth culture.

Finland’s Track Record

At 0.19% Finland boasts one of the lowest Infant Mortality Rates in the world as well as lowest income inequality of the EU. But it’s more than just economic indicators for household — the government is very much involved with prenatal mothers by providing the support needed to successfully deliver and raise a healthy child. Since 1949, Finland has insured every child has an equal start to life with a program that delivers a care package for all expectant mothers. And while some might argue that their taxation system is much higher than the United States, that is merely a misconception – it is the same format as the U.S. One interesting thing to note, however, is that Finnish society favors midwifery to the United States medical model, with nearly 80% of newborn births assisted by a midwife.

At 0.19% Finland boasts one of the lowest Infant Mortality Rates in the world as well as lowest income inequality of the EU. But it’s more than just economic indicators for household — the government is very much involved with prenatal mothers by providing the support needed to successfully deliver and raise a healthy child. Since 1949, Finland has insured every child has an equal start to life with a program that delivers a care package for all expectant mothers. And while some might argue that their taxation system is much higher than the United States, that is merely a misconception – it is the same format as the U.S. One interesting thing to note, however, is that Finnish society favors midwifery to the United States medical model, with nearly 80% of newborn births assisted by a midwife.

Japan’s Approach

There are only 1.9 deaths for every 1000 newborns in Japan, that’s nearly ⅓ of the rate of the United States (5.8). A bit closer to the U.S. in terms of poverty rate and income inequality, that still doesn’t account for their IMR being nearly 3 times lower. The birthing culture is found to be drastically different. Japanese women, stemming from Buddhist belief that labor pain is preparation for the difficulties of motherhood, opt out of painkillers and decline use of an epidural. Fathers must have taken a prenatal class to even be allowed in the delivery room.

There are only 1.9 deaths for every 1000 newborns in Japan, that’s nearly ⅓ of the rate of the United States (5.8). A bit closer to the U.S. in terms of poverty rate and income inequality, that still doesn’t account for their IMR being nearly 3 times lower. The birthing culture is found to be drastically different. Japanese women, stemming from Buddhist belief that labor pain is preparation for the difficulties of motherhood, opt out of painkillers and decline use of an epidural. Fathers must have taken a prenatal class to even be allowed in the delivery room.

On the contrary, women in the US are rarely given alternative options. Prenatal doctors prescribe medications, order vaccinations, and schedule medically induced labor without exploring more natural methods. As a result, these women, regardless of background, face pregnancy complications, health risks, and sometimes even death.

Cuba’s Surprising Stats

Cuba ranks 68th out of 183 countries in the Human Development Index and 95th out of 183 countries in GDP per Capita. Yet despite being far less wealthy, their Infant Mortality Rate is nearly 22% lower than that United States. So how is it that a nation with fewer resources have better IMR than resource rich nations such as the U.S. and Canada?

Cuba ranks 68th out of 183 countries in the Human Development Index and 95th out of 183 countries in GDP per Capita. Yet despite being far less wealthy, their Infant Mortality Rate is nearly 22% lower than that United States. So how is it that a nation with fewer resources have better IMR than resource rich nations such as the U.S. and Canada?

In 2010, an APHA (American Public Health Association) Delegation traveled to Cuba to find out why. They found that the Cuban people believe that individual health care equality is a right and that it is the government’s responsibility to provide that. In agreement, the government shifted to a public health and risk management ideology. In doing this, the aimed to not only reduce preventable illnesses and lower IMR, but look at the population as a whole and eliminate risk factors that contribute to these issues, such as binge drinking, teenage pregnancies, etc.

With a sensible public health policy, governments don’t need to spend as much taking care of a society that makes poor decisions. Cuba chose to prioritize access to clean water, reduce obesity rates, provide support for mental health, and focus on other public health issues, rather than simply pay for everyone’s bills. With a more proactive public health care approach they have been able to re-allocate resources to providing more care for an aging population and unpreventable genetic diseases.

However, in the United States, opponents of universal health care argue that they shouldn’t have to pay for other’s poor life choices, that it would create even more delays in receiving health care, and that people without health care can simply go to an emergency room. Proponents argue that it is a right and obligation of the government. But looking at the Cuban Health Care model of preventative medicine to limit health care costs, (contraceptives will always be cheaper than giving birth) and spending only what’s necessary seems to be an agreeable compromise.

Potential Improvements

The United States spends more on health care than any other nation on Earth, yet nearly 6 out of every 1000 children born here do not make it past the first few days. Comparing Finland, Japan, and Cuba, we can see that lower socioeconomic status alone is not responsible for high infant mortality rates cultural and political influences are just as important.

The United States spends more on health care than any other nation on Earth, yet nearly 6 out of every 1000 children born here do not make it past the first few days. Comparing Finland, Japan, and Cuba, we can see that lower socioeconomic status alone is not responsible for high infant mortality rates cultural and political influences are just as important.

Starting with small steps like access to education, contraceptives, health screening and possibly adding home environment assessment for at-risk neighborhoods, could help those most at-risk for SIDS and Preterm Birth.

Efforts to de-medicalize birthing practices, especially among minority and low-income women, could help reverse the disturbing trend of rising infant and maternal mortality in the US. This brief comparison of the US with other countries birth cultures clearly indicates there is much more to a countries’ health outcomes than their healthcare.

Join the Conversation