November is National Smoking Cessation Month (Don’t forget to quit smoking)

Smoking causes cancer. Everybody knows that. More significantly, everybody knows that everybody knows that. It follows unsurprisingly then that campaigns to get people to stop smoking produce diminishing returns as peek awareness is met and sustained. Cessation campaigns are important as younger generations advance, yet there remains an equilibrium of adult smokers that can’t or don’t quit despite being fully aware of the overwhelming evidence that smoking is bad for them. Continuing to assault this last bastion of holdouts with an unrelenting barrage of gruesome imagery and facts is one path forward to mitigating the harmful effects of tobacco use. Another way would be to implement social and economic reforms that seek to minimize or eliminate where possible, the social causes that keep this staunch demographic bound to their fate.

We can’t just keep telling smokers to quit smoking. It’s not enough. The message is clear that the resulting health-related problems are their own fault because of their own individual choice to smoke. The added shame of feeling at fault for your own circumstances is a causal determinant that induces poor health outcomes. Focusing on smoking as an individual risk factor, while downplaying the underlying causative social factors, exacerbates poor health by making disadvantaged women feel even more helpless. Even when some women do quit smoking, it doesn’t solve the upstream problems that are the fundamental cause of both why they smoke, and why they are vulnerable to health adversity.

Let’s start with what everybody knows. Smoking can kill you.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), cigarette smoking is the number one risk factor for developing lung cancer, and is linked to 90% of lung cancer deaths,1 40% of all diagnosed cancers,2 and 20% of all deaths in the United States.3

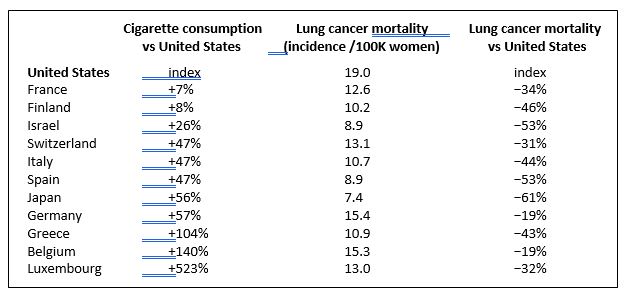

Smoking is inarguably bad for you. Nevertheless, it is worth noting the reciprocal observation that smoking does not cause cancer in everyone who smokes. 85-90% of lifetime smokers do not get lung cancer,4-6 so it matters to ask why some smokers get cancer or suffer from other poor health outcomes associated with smoking, when so many others do not. And while it’s true that an individual’s level of cigarette consumption increases the risk of developing lung cancer,1 it’s not a simple case of more is worse. Several countries have significantly higher cigarette consumption rates than the U.S., but have a much lower incidence of lung cancer mortality. For example, cigarette consumption in the U.S. is significantly lower than in Japan, yet lung cancer mortality in U.S. women is 2.5 times higher than it is for Japanese women. It’s not because Japan has more effective treatment (morbidity is also higher in the U.S.), and it’s not because cigarettes don’t cause cancer (they do).

There is no doubt that smoking is bad for you. But how bad it is for you depends on where you live.

The table above shows that lung cancer mortality is not always linearly proportional, and not even always positively correlated to cigarette consumption.7,8 This is especially true when considering the different material and social conditions that vary among groups of people at the population level.7,8 Studies often eliminate social factors as confounding factors in order to focus solely on a single individual risk factor (i.e. smoking) to explain its contribution to disease burden. But social factors are themselves causative factors in health disparities at every level, and are the primary determinants of who gets sick and who does not. 9 The World Health Organization calls this the social gradient of health.

Women who smoke in the U.S. are especially disadvantaged compared to their international peers.

Women who smoke in the U.S. are especially disadvantaged compared to their international peers.

Smoking is much worse for women who smoke while living in the U.S., and that’s because women in the U.S. are disadvantaged by their social setting in a way that creates a cumulative health burden. As a result, women in the U.S. are more vulnerable to the harmful effects of any and all toxic assaults, including the toxic ingredients of cigarettes.

The World Health Organization has extensively researched the social causation of disease,9,10 and although more needs to be done, they have identified causative factors that function as the primary determinants of health and disease:

- The Social Gradient. Those lower down in the social hierarchy are more vulnerable to poor health outcomes. This effect is more pronounced the steeper the social and economic hierarchy is within a country. The U.S. has the steepest income gap between rich and poor of any developed nation. There is an identifiable social distribution of health: Those at the top have it, those at the bottom do not.

-

Stress. The chronic stress that women often endure raises their baseline cortisol levels and blunts their stress response such that their bodies are in a constant state of stress. This raised baseline for stress is not felt acutely but accumulates as a health burden throughout a woman’s life, making her vulnerable to disease.

Stress. The chronic stress that women often endure raises their baseline cortisol levels and blunts their stress response such that their bodies are in a constant state of stress. This raised baseline for stress is not felt acutely but accumulates as a health burden throughout a woman’s life, making her vulnerable to disease.

- Early Life. “A good start in life means supporting mothers and young children: the health impact of early development and education lasts a lifetime.”10

- Social Exclusion. Feeling excluded creates a state of chronic stress which becomes a cumulative health burden. Racism and gender biases need to be eliminated to prevent the deleterious health effects of exclusion.

- Work. Women need to have control over their lives. Job insecurity and stress at work impairs the immune system and increases the risk of cardiovascular disease.

-

Social support. Women who have strong social networks within their families, communities, and workplace have better health, and respond better to health challenges.

Social support. Women who have strong social networks within their families, communities, and workplace have better health, and respond better to health challenges.

- Addiction. Women who suffer deprivation, violence, exclusion, and/or chronic stress, often turn to alcohol, drugs, or tobacco as a means to self-medicate. There are other reasons why people become addicted but it has been shown, for example, that smoking correlates with every marker of deprivation that can be quantified.9 Additionally, smoking correlates more strongly with an individual’s social destination than it does with her circumstances of origin, meaning the real question isn’t why people start smoking, but why some don’t or can’t quit.9 They are in need, and those needs are not being met.

If health policy effectively addressed the social and economic needs of women in the U.S., not only would deaths from lung cancer decrease, the morbidity and mortality rates of almost every other disease would decrease as well ─ even if the rate of individual risk, such as smoking, did not decrease.

If health policy effectively addressed the social and economic needs of women in the U.S., not only would deaths from lung cancer decrease, the morbidity and mortality rates of almost every other disease would decrease as well ─ even if the rate of individual risk, such as smoking, did not decrease.

We can and should continue efforts to reduce the amount of tobacco use in the U.S., but we should also implement solutions that make women feel empowered with respect to their lives. Women need to have control over their bodies, more security in the workplace and in their social interactions, in order to avoid becoming vulnerable to all the things out there that might harm them, including cigarettes.

The current public discourse, as well as legislative efforts geared toward improving health in the United States, are concerned almost entirely with providing access to healthcare, which in turn provides a means for individuals to pay for medical visitation and treatment. It’s not enough. The doctor can only intervene on an individual level, and so the clinical approach is limited to prescribing a remedy based on individual risk factors and biological screening indicators, along with early detection, and treatment. The smoker is told to quit smoking, maintain a healthy diet, and exercise. If she gets cancer, the clinician and the clinic are there to treat her cancer. Smoking cessation campaigns buttress the same message.

For sustainable improvements in health, we must alleviate the social disadvantages that burden women in the U.S. with accumulated health vulnerabilities. Of course we should provision healthcare, but we should also seek to keep people from needing it in the first place. The primary determinants of disease are social and economic. The remedy must also be social and economic.

Join the Conversation